In this blog, we look at cremation urns, what they are, and what they mean for archaeologists.

Our excavations along the route of the new A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme have led us to uncover fascinating stories about Cambridgeshire’s past populations and the discovery of human remains plays a big part in that.

It’s not unusual to find cremation burials; both urned and unurned in the British archaeological record. They provide information of specific mortuary practices which can help us to understand past peoples’ relationship with death. The vessels can also teach us about trade and about local resources. For example, whether the urns were made locally or imported, what they are made from and how.

What is a cremation urn?

A complete Bronze Age collared cremation urn (c) Highways England courtesy of MOLA Headland Infrastructure

A cremation urn is a vessel in which the cremated remains of an individual would have been placed. Urns vary in size and style throughout different time periods.

Cremation urns from the Bronze Age such as the one pictured here were discovered on the A14 scheme along with cremation burials dating to the Romano-British period (43-410 AD). However, cremations seemed to become less common as time went on.

What do cremation urns mean for archaeologists?

The cremation process would have taken place on a funerary pyre. Cremated remains recovered from this process are therefore often more coarse, with fragments of bone surviving. These pieces of bone can be studied by human osteologists and can provide really useful information about the individual or individuals which in turn can help us to better understand the population.

However, it’s not just the human remains that are interesting, other objects within the vessel, the pottery that the it is made from, its form and its decoration provide archaeologists with crucial information for dating.

How are cremation urns studied?

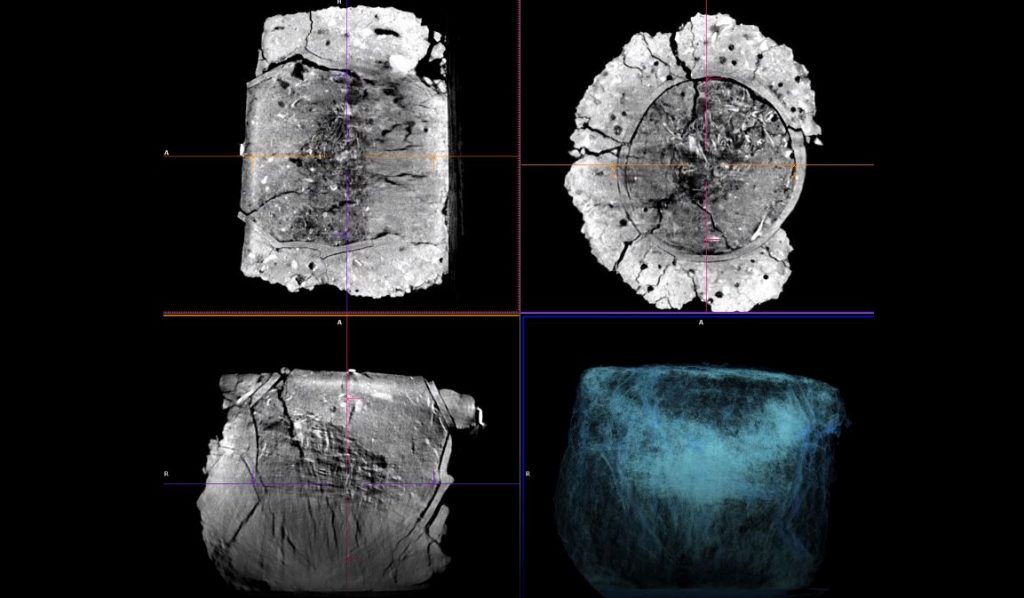

CT scans courtesy of Dr Andrew Gogbashian, Paul Strickland Scanner Centre

This is a CT scan image of a large cremation urn discovered during the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme. It was block lifted on site to ensure it wasn’t damaged, and to preserve any associated evidence of artefacts or environmental material in the soil around it and taken to the Paul Strickland Scanner Centre in Middlesex to be scanned so that we could see what we might expect to find within or outside it, where any contents lie, the condition of the vessel, its profile and orientation in the ground, before micro-excavating the soil and remains at the MOLA Headland labs.

Prehistoric pottery was fired at low temperatures and so typically it is extremely soft and fragile when excavated. Added to this, some of the vessels found during the A14 excavations were particularly large and fragmentary, so it was necessary for our conservators to record and consolidate areas of the vessels to protect them at the same time as recording and excavating the soil fills.

The pottery and contents are now with our specialists for assessment, and as we move through the post-excavation process we’ll be documenting our discoveries.

Join us on our journey!

- Twitter: @A14C2H #A14Archaeology

- Facebook.com/A14C2H/ #A14Archaeology

- Find out more about the A14C2H improvement scheme here

The archaeological programme for the Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme is being carried out by A14 Integrated Delivery Team on behalf of Highways England.

0 Comments

Leave A Comment