Josephine Adams is a historical researcher and specialist in burials in 19th century Birmingham. In this blog she explores past excavations in Birmingham and the potential of the Park Street burial ground excavations, being undertaken by MOLA Headland on behalf of LM for the HS2 project, to allow a better understanding of the development of the UK’s second largest city.

For many years, the area that was once the Park Street burial ground was considered an untidy and neglected part of the city, a place of little value. It is important to remember that, in the early 19th century, Park Street was significant as the over-flow burial ground for the church of St Martin in the Bull Ring: the focal point of the growing industrial town of Birmingham. As such, the people buried there are part of the story of Birmingham’s rise as an industrial powerhouse.

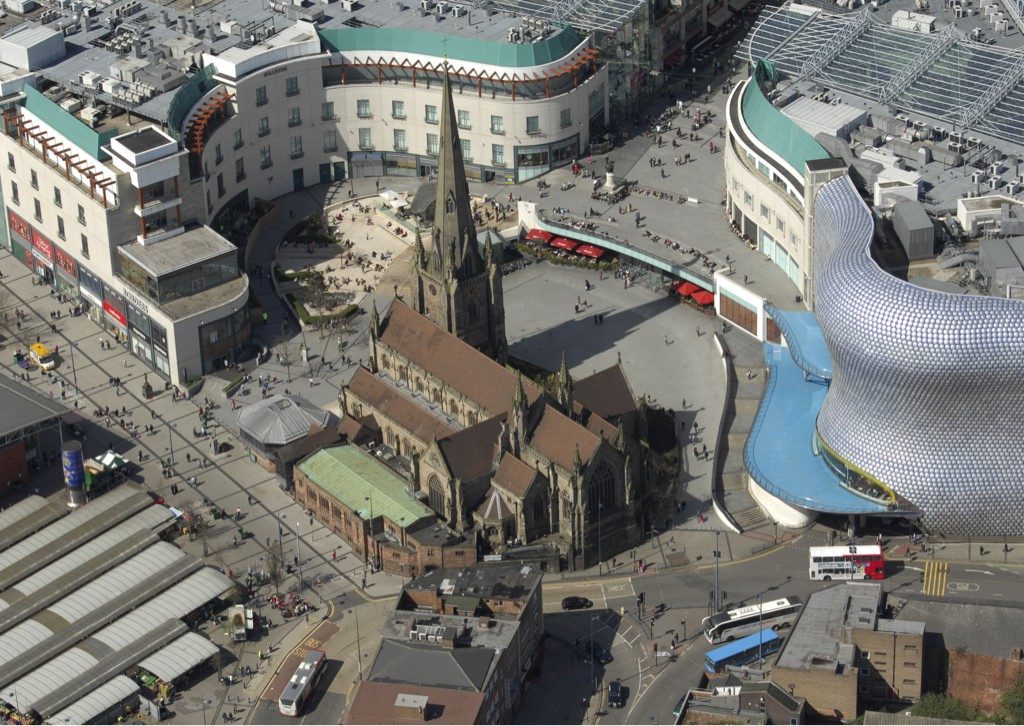

Aerial view of St Martin-in-the-Bullring, Birmingham

St. Martin’s Churchyard

In 2001, whilst working for Birmingham Archaeology, I was part of the team that undertook an excavation of the north-western part of St. Martin’s Churchyard in Birmingham City Centre, in advance of the new Bullring shopping centre. Initially, I was involved in the logistics of the excavation but subsequently undertook historical research relating to the site and its burials.

The burial ground was in the same parish as Park Street burial ground and in use at the same time, so there is great value in looking at the results of both digs together.

The St. Martin’s Churchyard findings were published in 2006. A total of 857 burials were excavated at the site. 734 were graves cut into the earth, but within the site there were several brick vaults and brick-lined graves that contained a further 123 burials.

Such a large sample resulted in valuable research in three complementary areas: anthropological research of the burials, research relating to the funerary trade and burial practices, and documentary research on named individuals in the vaults.

Connections

So, what further connections are there between this project and the Park Street excavation?

Apart from their historical and chronological links (see our Park Street burial ground and Birmingham’s population expansion blog for more details) and their geographic proximity, both are modern excavations undertaken to the highest standards by professional archaeologists for excavations undertaken ahead of development. This means there is a wealth of rich archaeological data and material to study and interpret.

Following excavation

The work that follows any archaeological excavation is vital to place the site in its local and national context, and sites that include human remains can provide an in-depth analysis of life and death of the time. When the final report was published, St. Martin’s was the first extensive excavation of a burial ground of any period to have taken place in Birmingham. The results provided insights into life in the city in the 18th and 19th centuries when industrialisation accelerated and the town was rapidly changing.

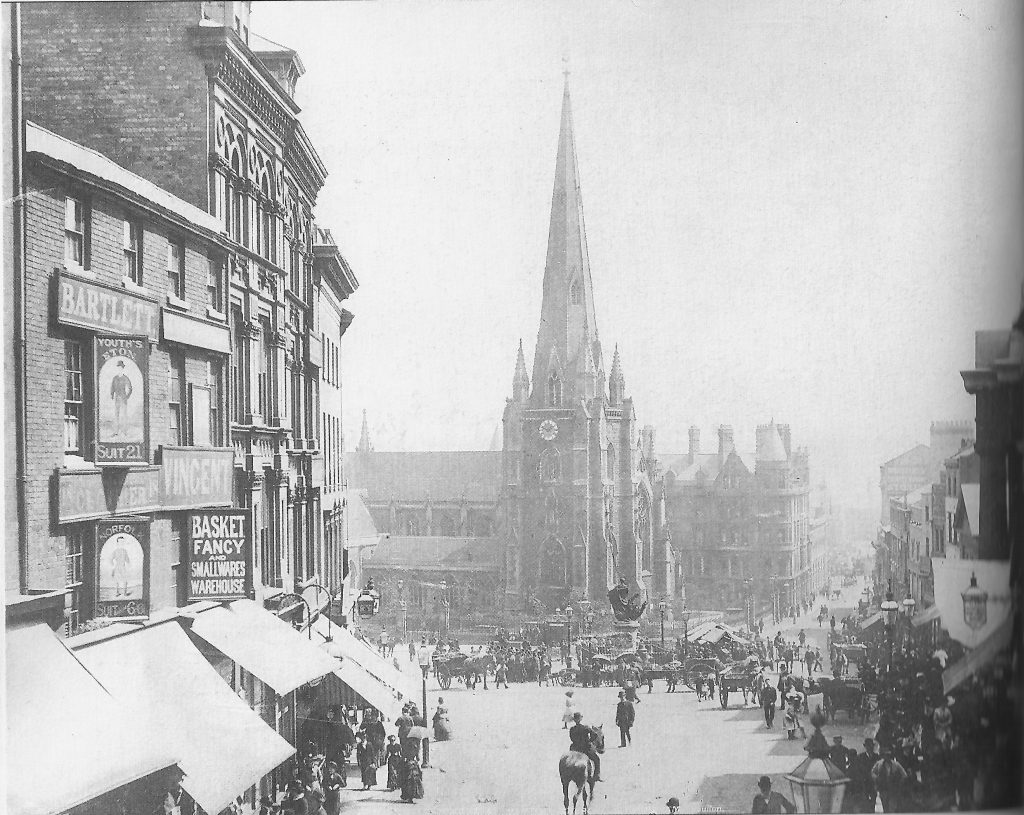

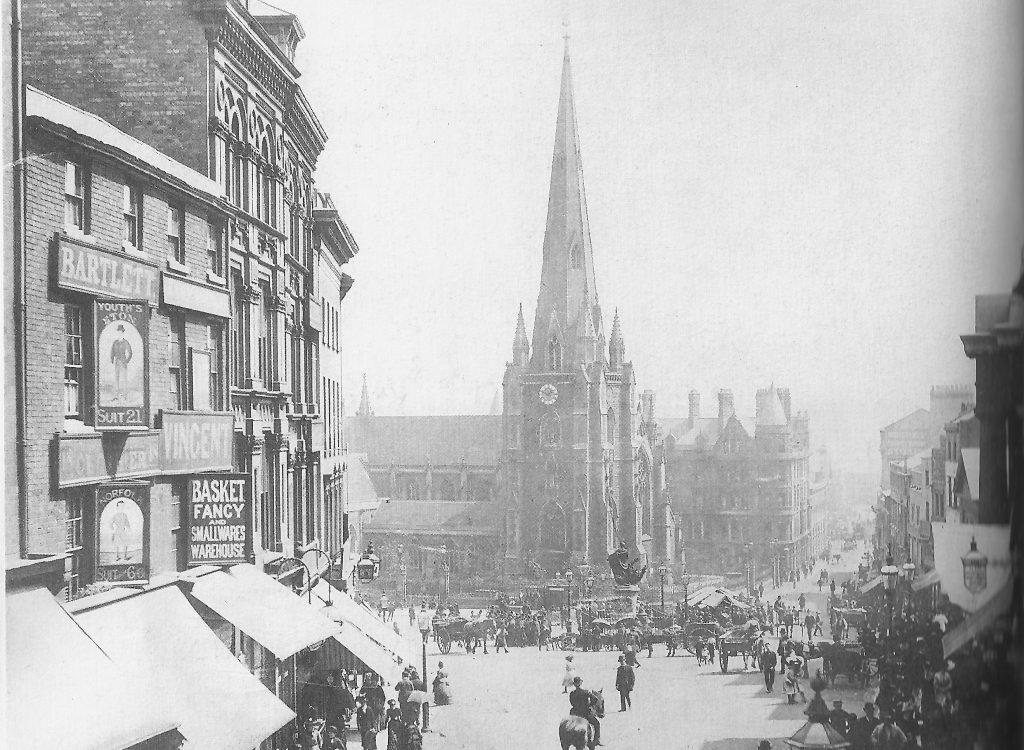

The bull ring and parish church of St Martin, Birmingham, 1880s, unknown photographer

Studying the human bone was the largest part of the post-excavation project. The demographics and family links of the people buried were analysed and further study of the bone revealed how living in a densely populated urban area had affected the people. Vitamin D deficiency was seen in both adults and children, almost certainly indicative of high levels of pollution and poor housing cutting out light. Inadequate diet, which affected large sections of society, would also have contributed to vitamin deficiencies. Dental health, including the use of false teeth, was noted in the St Martin’s burial population as well as examples of medical interventions apparent on the skeletons, such as autopsy.

Amongst the health conditions that were more obvious on the skeletons were joint diseases such as arthritis and gout. There was also evidence of tuberculosis, sinusitis and brucellosis (an infection, very rare today, caught from eating unpasteurised milk and cheese), showing close contact with animals. Bone fractures were also examined and the causes of traumas considered, with damage inflicted through work related accidents, play (children) or violence.

Research was carried out on the coffins and coffin furniture from St. Martin’s and will also be important at Park Street, potentially showing links with local industries. It was fortunate that within the burial vaults at St. Martin’s there were some readable coffin plates that enabled research on the individuals buried there. This complemented analysis of skeletons and provided a more rounded picture of people and their roles in Birmingham society at that time. The number of skeletons excavated at Park Street is much larger than at St. Martin’s, and together there is significant potential for research.

Those who came to rest at both burial grounds were from the same parish, and some may even have been related. They would have experienced similar problems, illnesses and accidents, as well as the same joys and the same triumphs. The post-excavation process is where we start to understand these details, and studying the larger burial population from Park Street will undoubtedly enhance understanding of the St. Martin’s dig, increasing our knowledge of life and death in 19th century Birmingham.

St Martin’s uncovered: investigations in the churchyard of St Martin’s in‐the‐Bullring, Birmingham, 2001. M. B. Brickley, S. Buteux, J. Adams & R. Cherrington. Oxbow Books, Oxford, UK, 2006. 288 pp.

The archaeological programme at Park Street in Birmingham is being carried out by our experts on behalf of LM for HS2 Ltd. To find out more about the programme visit www.hs2.org.uk or for information on what is going in your local area head to Birmingham’s Commonplace.

Explore the archaeology programme on social media with #HS2digs

0 Comments

Leave A Comment