Archaeological excavations at the site of the 19th century Park Street burial ground in Birmingham are up and running. Part of wider archaeological investigations taking place along the Phase One stretch of the HS2 rail route, the Park Street site is located on what will be the Birmingham Curzon Street railway terminus.

The team on the ground is made up of our experienced archaeologists and osteologists (experts in studying human remains), supported by Laing O’Rourke Murphy (LM) and the Design Joint Venture DJV (WSP and Ramboll). We anticipate that we’ll uncover well over 8000 burials, believed to be the largest collection of 19th century burials outside of London. The excavation is taking place under a purpose-built temporary shelter, to shield our delicate work from view and to preserve the dignity of the remains.

As the dig progresses we’ll be sharing our findings and looking at how the site and the people buried here connect to the wider history and story of Birmingham. But for now, read on and we’ll tell you a little about how Park Street developed, and what we’re hoping to find.

The earliest map showing Park Street – made by William Westley in 1731 – reveals that the site was once mostly covered by an orchard, bounded by what appear to have been vegetable-growing fields to the east, and a small plot of buildings to the west.

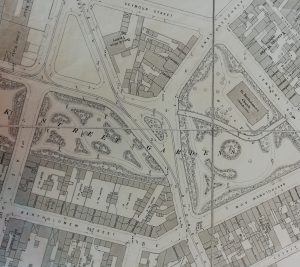

First edition Ordnance survey map of Birmingham, 1889

By the time the First Edition Ordnance Survey map was drawn, a little over 150 years later, the area had been transformed and was surrounded by tramlines, railways and densely packed courtyard houses.

In 1807, the land at Park Street was bought by the church, to set up an overflow cemetery for St Martin-in-the-Bullring. The cemetery opened shortly after, with the first burial written in the church register in 1810. The burial ground was only open for 63 years, closing to public burial in 1873. By this time, the burial ground had become rundown, and in 1880 the Corporation of Birmingham took the site over and opened it as a public park.

It’s not known exactly who was buried at Park Street as the burial register for the church also covers the graveyards at St Martin and St Bartholomew’s. However, the hope is that some burials will have name plates which will help us to build detailed biographies connecting names to wider social histories. We want to explore questions about the development of this significant corner of Birmingham, including:

What industries were emerging? Where did the entrepreneurs and labour force migrate in from? How did this centre of transportation and communication facilitate the rapid growth of the industrial revolution and make Birmingham a vital hub?

Although we won’t be able to identify the majority of the people buried here, skeletal remains will tell us a great deal the effects of life in 19th century industrial Birmingham on the population of the time. By analysing the remains, our osteologists should be able to build a picture of the kinds of lives people led, some of the diseases and injuries they suffered from, and perhaps even what they ate and where they came from by using stable isotope analysis. Our initial investigations have already identified evidence of diseases including probable scurvy and possibly rickets.

When our research is complete the human remains will be reburied on consecrated ground in the Birmingham area.

A team of expert osteologists are studying the skeletons from Park Street in Birmingham

Objects placed into burials are already proving to be a rich source of information. One burial contained a bone handled knife and two contained dinner plates, while a fourth contained a broken wine glass. These finds provide insights into the types of burial rituals, traditions and practices that were carried out during the 19th Century. In examining these closer, we can compare and reflect to see if any of these artefacts are still around today, or if they remain tied to a particular era or circumstance.

We have also been finding items more likely to be associated with the site’s use, starting in Victorian times, as a park. Thus far these have included clay tobacco pipes, glass bottles, crockery and buttons. When digging deeper into older layers, we hope to find evidence of earlier uses in this locality, including perhaps the boundary and associated features of the Medieval Deer Park (Little or Over Park), that has been indicated on old maps.

Clay tobacco pipes

To find out more about the HS2 archaeology programme visit www.hs2.org.uk or for information on what is going in the Birmingham area or how you can get involved head to https://hs2inbirmingham.commonplace.is/.

Explore the archaeology programme on social media with the #HS2digs.

3 Comments

Will there be any DNA tests of the individual bodies from this burial ground? My family were living in this area and I have had my DNA recorded with Ancestry.co.uk

So interesting..didnt even know there was a buriel pkace there..x

Leave A Comment