Along the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme, we’ve uncovered thousands of items that provide insight into their owners. We have also learnt a great deal about the lives of the objects themselves. In this blog, find out from Senior Specialist in Prehistoric and Roman Finds, Michael Marshall, about a couple of Roman objects with particularly interesting biographies.

The A14C2H excavations have recovered thousands of objects which can help us to investigate the lives and identities of people who lived in Cambridgeshire in the past. However, it is important to remember that artefacts have their own ‘lives’ and that they didn’t always have a single fixed meaning. Their biographies are made up of a series of stages that we need to try and reconstruct, such as manufacture, exchange, use and discard. These objects might have touched the lives of many different people and changed their significance along the way. This blog focuses on two very different Roman artefacts that I think might have had long and interesting lives: a broken sherd of glass and a jet amulet.

From the table to the grave: a treasured sherd of polychrome glass

Roman glass was not a common find on the rural Romano-British settlement sites along the scheme and most fragments come from simple bottles made of naturally-coloured blue-green glass. However, a handful of more elaborate vessels stand out that would have graced the tables of their owners and perhaps impressed their guests.

One example is a polychrome millefiori bowl, probably dating to the 1st or 2nd century AD and found in the area between Conington and Fenstanton. This beautiful vessel is now broken and only a single fragment survives to hint at the fine dining which might have taken place somewhere nearby. However, the final resting place of this broken sherd was not a rubbish pit associated with a settlement, but a late Roman burial ground.

A fragment of polychrome glass found in a Roman burial, © Highways England, courtesy of MOLA Headland Infrastructure

It is possible that this was a long-forgotten piece of rubbish, and simply became accidentally incorporated during the backfilling of the grave. However, it is an interesting coincidence that this distinctive, colourful and highly patterned sherd was found in such a significant context. Was it deliberately placed within the grave?

A similar discovery in another Roman burial lends some support to this idea. Several sherds of polychrome glass were recovered from the burial of a child in a cemetery outside Roman London. They formed part of a group of objects deliberately placed within a sealed coffin. Clearly, colourful luxury glass vessels could retain some significance even during their ‘afterlife’ as broken sherds.

The A14 burial was that of an adult and the meaning behind these two finds might not be identical. One can imagine a coloured piece of glass being collected and treasured simply for its colour and pattern, in the same way as people might pick up interesting stones or fossils, and such curious objects are also sometimes used as amulets in the Roman period. Alternatively, could it be a token keepsake of the original vessel? Perhaps a gift or treasured object that held emotional significance for the deceased before it broke? Further research may reveal other examples of glass sherds which have been deliberately deposited in burials. If so, it might be possible to explore the reasons behind this practice in more detail.

Well-worn: the story of a Roman amulet

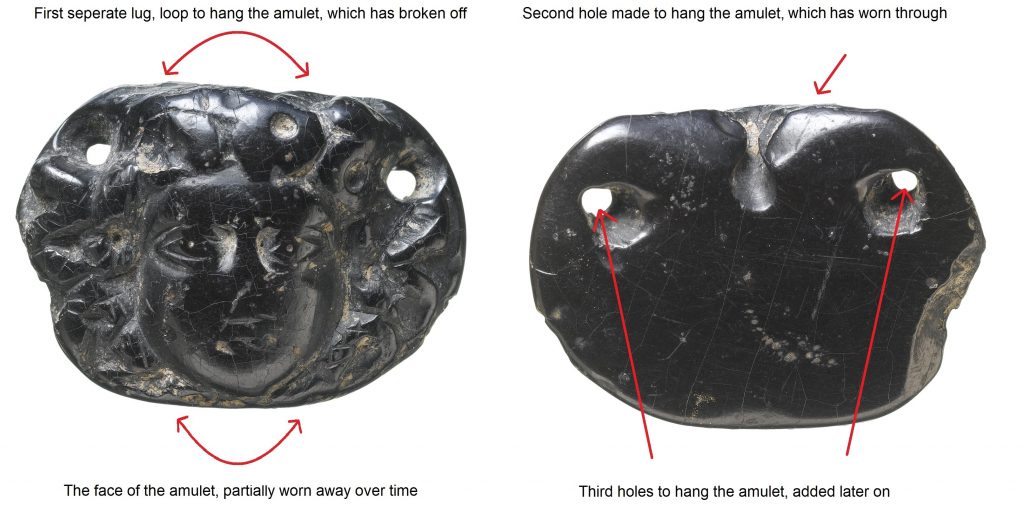

At another site near Brampton, a late Roman amulet was discovered. It is made of jet, a black, shiny and electrostatic material that was considered to have magical powers to ward off bad luck. It probably came from the Whitby area of Yorkshire and it is carved with the face of the gorgon Medusa, whose fearsome appearance was believed to ward off the evil eye.

Roman jet pendant depicting the gorgon Medusa, showing evidence for extensive wear and repair. © Highways England. Courtesy of MOLA Headland Infrastructure

These magical amulets were probably expensive objects and are more normally found within high status female burials, especially at large Roman cities such as York and London. The context in which this object was found is atypical and when we look closer, evidence of an unusually long and complex life begins to emerge. The surface of the amulet is very worn, perhaps due to it being handled over a long period of time and/or rubbed by its owner(s) to generate a ‘magical’ electrostatic charge.

The perforations by which it was suspended, have been broken or worn through and then replaced on two separate occasions. These features suggest it had a longer life than many other amulets of the same type, perhaps because it was passed on, or handed down through the generations, rather than being buried with its original owner.

Fragment of a Saxon antler pendant © Highways England. Courtesy of MOLA Headland Infrastructure

The amulet was found in an archaeological feature of a later date. within which a fragment of decorated antler pendant/ or amulet of Saxon date was also found. Could they have been used and deposited together a century or more after the pendant was first made? This might explain both the extensive wear and the unusual find location; as the importance of towns declined between the late Roman and early Saxon period urban communities may have dispersed.

Over time, as the image of Medusa became more worn, and Britain’s Roman connections weakened, so too some of the original mythological meaning of the pendant may have been lost. However, the evidence of its long life and possible association with another amuletic object, suggest that this ancient object retained some significance, perhaps as a trusty heirloom worn alongside newer more fashionable styles of amulets.

Join us on our journey!

- Twitter: @A14C2H #A14Archaeology

- Facebookcom/A14C2H/#A14Archaeology

- Find out more about the A14C2H improvement scheme here

The archaeological programme for the Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme is being carried out by A14 Integrated Delivery Team on behalf of Highways England.

0 Comments

Leave A Comment