The numerous archaeological surveys we have carried out on the A14 Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme have revealed a huge range of archaeology, dating from the earliest hunter-gatherers to the Second World War. Most recently, excavations by MOLA Headland Infrastructure have revealed new insights into the Roman Ceramic Revolution in southern Britain. Pottery Specialist Adam Sutton investigates…

Continuing work on the A14 post-excavation analysis is shedding new light on the old question once succinctly put by John Cleese: “what have the Romans ever done for us!?”, with the discovery of more than 40 early Roman pottery kilns. Though the Monty Python team saw no need to have their Judean rebels mention pottery production – the wine was clearly far more important – the Roman occupiers of Britain brought with them new and more complex forms of pottery industry.

Before the Roman invasion in AD 43 there is little direct evidence for pottery production, despite pottery being a very common find on Iron Age sites in many areas of southern Britain. This is because of the ‘low tech’ nature of pottery making for much of the Iron Age: pots were made from coils of clay, and fired at relatively low temperatures in bonfires or the household hearth. In the vast majority of cases barely any archaeological remains will be left for us to identify with confidence. Pottery making was probably done occasionally, when new pots were needed around the home. There appears to have been no market for the trade of pottery, and evidence for the movement of pottery between sites seems likely to be the result of gifting or the exchange of the goods which the pots contained.

- An updraught kiln dating to the mid-first century AD phase on an A14 site near Brampton. This is a view of the front of the kiln, which has been truncated from its original height due to subsequent activity, with the stoking area in the foreground.

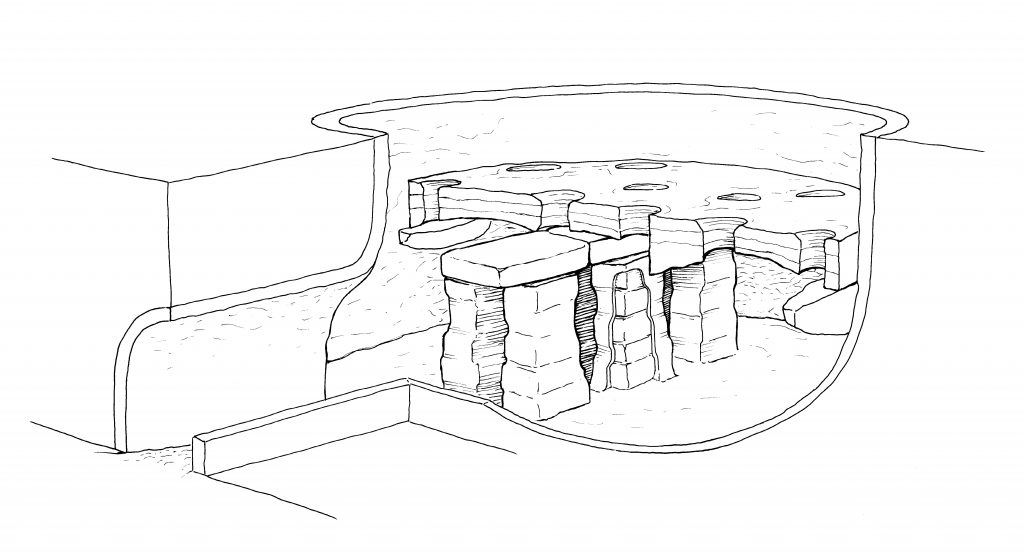

- The same kiln, this time a view of the interior of the main chamber. A temporary floor will have been built within the chamber from prefabricated ‘kiln furniture’, and the pots stacked on top.

By the time of the Roman invasion this was evidently changing. Among the innovations of the first century AD were the first purpose-built pottery kilns known in Britain. These are relatively complex structures built from clay (and sometimes stone) which allowed potters to fire wheel-made wares to temperatures approaching 1000 degrees centigrade. The pottery being made improved rapidly in quality, and was able to be made in larger quantities resulting in a surplus which could be traded at market, or used as packaging for the movement of other goods that needed to be shipped around.

More than 40 Roman pottery kilns were found during the A14 excavations, most of these being in a small area to the west of the modern village of Brampton. Two things are significant about pottery production on the A14: firstly, the sheer scale of the industry and, secondly, its early date. Pottery being made in the A14 kilns dates to around AD 60 onwards – less than twenty years after the invasion – and several radiocarbon dates back this up. The number of kilns as well as associated structures (possibly workshops, drying sheds, etc.) shows that this was a significant industry. The potters of Roman Cambridgeshire were evidently quick off the mark in taking on the opportunities presented by new technology.

Though the emergence of this industry will have been part of longer-term processes of technological change beginning well before the Roman annexation, the A14 evidence shows that economic shifts were taking place in the aftermath of the invasion which led some craftspeople to intensify their operations and experiment with new ideas. We have more work to do to unpick how the A14 potters worked and how their industry was organised, with a range of scientific techniques at our disposal. No doubt we will need to wrestle with the old questions again: were the people of Roman Cambridgeshire pursuing the new opportunities provided by a ‘globalised’ empire, or having to keep up in the context of an economically dominant imperial regime? The answer to the question “what have the Romans ever done for us” seems likely to have been complicated, and the evidence from the A14 allows us to consider in detail what the working lives of these people were like in order to fully appreciate their part in this story.

A cross section diagram of a Roman updraught kiln showing the arrangement of a movable floor propped up on pilasters, on which pots would be stacked. Above ground level, a dome of clay and turf (not pictured) would insulate the load. A fire would then be set in the opening on the left (the ‘firebox’ or ‘flue’), the resulting heat being drawn up into the kiln by air currents.

Join us on our journey!

- @A428Cat#A14Archaeology

- facebook.com/A428BlackCat #A14Archaeology

- Find out more about the A14C2H improvement scheme here

The archaeological programme for the Cambridge to Huntingdon improvement scheme is being carried out by A14 Integrated Delivery Team on behalf of Highways England.

1 Comment

I can’t wait to find out more about the excavations of the A14. These are really interesting finds for a history fan like me.

Leave A Comment